Competency model: how to build it and why it is useful

Something has happened in recent years that has irreversibly changed work: skills are no longer a requirement, but the very infrastructure on which an organization stands.

We are seeing completely transforming roles, new technologies, hybrid teams that require completely different ways of collaboration.

In many cases, what is missing is not the right people, but the ability to understand what skills are really needed and how they combine to generate performance.

That is why more and more HR is returning to a tool that is as classic as it is indispensable: the competency model.

The Competency Framework is a tool that allows HR and managers to have a clear, shared vision of what it really takes to be successful in a role, team, or entire organization.

A critical tool especially when we consider that, according to McKinsey, 44 percent of organizations say they face or anticipate critical skills gaps in the next five years.

We can say that today, without a competency model, it becomes almost impossible to hire well, evaluate objectively, design growth plans or drive upskilling and reskilling programs.

Let's see how to build a skills model that is really useful and applicable in your company.

What is a competency model

A competency model (or competency framework) is a structured map that describes the skills, behaviors, and characteristics a person must possess to be successful in a role, team, or entire organization.

To simplify, we can define it as a system that allows HR and managers to measure and define the competencies required in a specific company in a clear, observable and replicable way, and to use them for selection, training, evaluation and development.

To understand how this logic comes about, we need only look at three fundamental contributions that have built the basis of all modern models.

Why does the concept of "competence" arise?

In the 1970s, David McClelland was the first to question traditional intelligence tests and assessments used in selection processes.

According to him, companies were wrong to measure "how smart a person is," when they should have been measuring which behaviors produce excellent performance.

This is where the modern concept of competence comes from:

a combination of observable behaviors that distinguishes those who perform better from those who perform average.

This view paved the way for all subsequent competency models: more objective, evidence-based assessments, not impressions.

A few years later, Richard Boyatzis extended McClelland's work by showing that excellent performance arises from an integrated set of:

- technical skills

- soft skills

- personal characteristics

- values and motivations

His model has become a standard in HR processes, especially in leadership development.

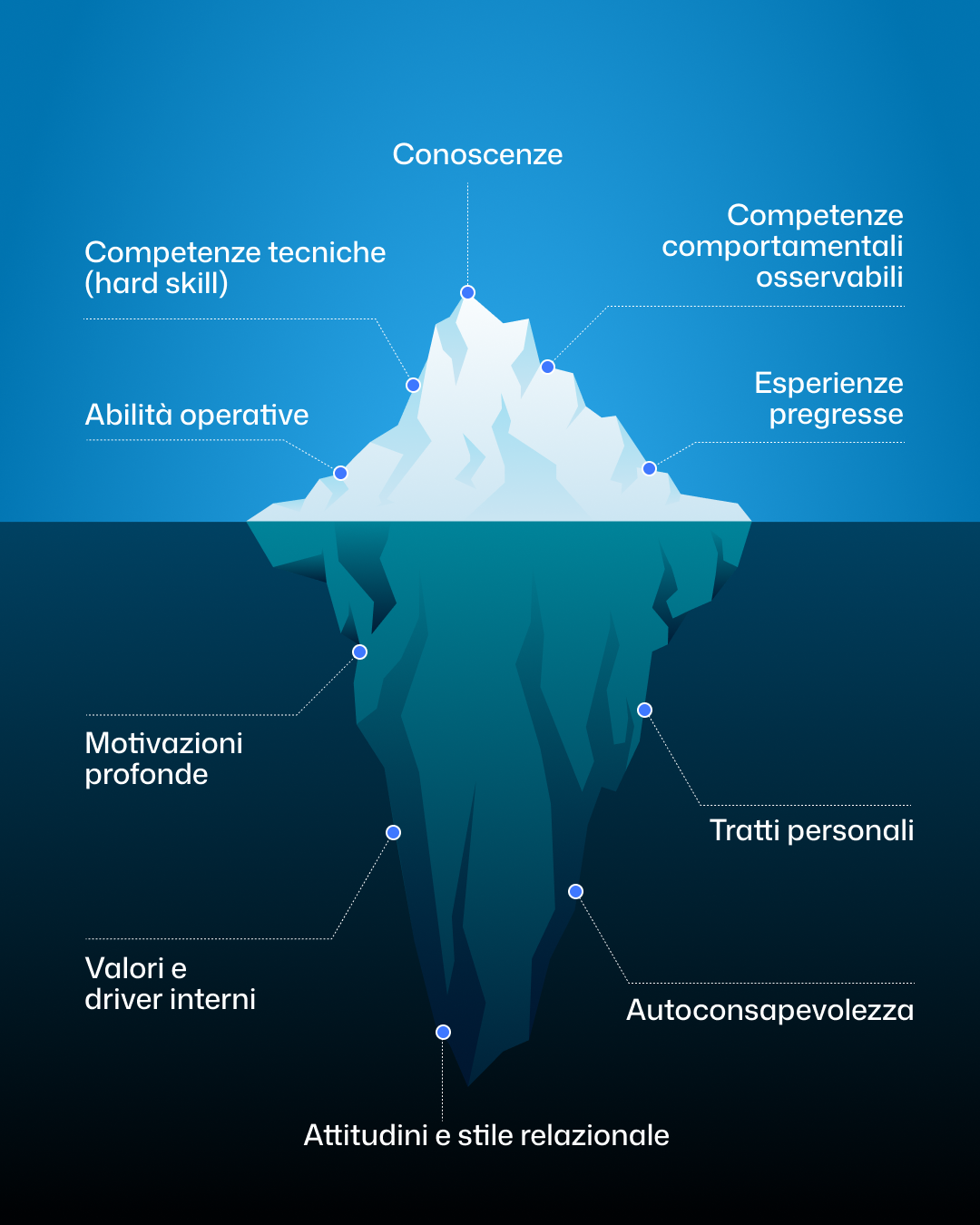

Spencer & Spencer's competency model: the "iceberg model"

When it comes to the competency model, the most famous reference is Spencer & Spencer, authors of the famous Dictionary of Competencies.

Their key insight is the iceberg model, which explains why some competencies are visible and measurable, while others work "below the surface."

According to the model:

- above the water level there are technical knowledge and skills (easy to observe and train);

- beneath the surface are traits, motivations, values, and attitudes (more difficult to change, but decisive for performance).

It is a model that many companies today use to create their own "catalog" of competencies and define internal development paths and role profiles.

What elements does a competency model consist of?

A competency model is a framework that defines how a successful person performs in a role or in an entire organization.

Therefore, if you have to build a model, you will need to include all the areas that really influence performance: technical skills, soft skills, managerial skills, values, and observable behaviors.

Here are the four dimensions to take into account.

Technical skills (hard skills)

Hard skills are the most easily observable and verifiable skills: they concern what a person knows and can do in technical-professional terms.

We specify that hard skills do not follow the logic of observable behaviors typical of soft skills.

They are assessed mainly through practice tests, drills, technical tests or instruments that measure operational knowledge and skills, not behaviors.

Any examples?

- Programming languages;

- data analysis;

- project management;

- accounting skills;

- Knowledge of specific tools (CRM, ATS, CAD, cloud platforms).

Soft skills

Soft skills are the behavioral and interpersonal skills that affect the way a person works, collaborates, and deals with complex situations.

Skills such as:

- effective communication;

- problem solving;

- collaboration;

- time management;

- adaptability;

- emotional intelligence.

If you are looking for even more specific examples of soft skills, read this guide.

Management and leadership skills

This category describes the skills needed to lead people, processes, and decisions.

Again, here are examples:

- Effective delegation;

- conflict management;

- results orientation;

- facilitation skills;

- Coaching and people development;

- strategic vision.

In a modern competency model, leadership is not limited to "directing," but also takes into account the ability to create healthy work environments, make informed decisions, and sustain change.

Expected values and behaviors

This dimension is often underestimated, but it is the one that really distinguishes an effective competency model from a purely descriptive one.

Here they fall in:

- organizational values;

- ethical principles;

- Expected behaviors in line with the corporate culture;

- required mindset (e.g., proactivity, responsibility, innovation orientation).

We can call them the bridge between "who we are as a company" and "how people are expected to work."

Many modern models (think Levati's competency model) provide precisely this level to ensure cultural coherence and alignment between behaviors and mission.

It must also be said that, in many models, values and competencies are kept separate: the former define the corporate culture, the latter describe what it takes to be successful in a role.

Unifying them or keeping them separate is a design choice that depends on the level of HR maturity and the objectives of the model.

How to build a competency model

If you manage people, roles, and HR processes, you already know how difficult it is to make decisions based only on generic job descriptions, subjective assessments, or manager perceptions. That's exactly what a competency model is for: creating a common, clear and measurable basis for selection, development, internal mobility and performance.

An important clarification: a competency is always defined and assessed through observable behaviors.

You do not evaluate the label ("problem solving"), but what a person does: how he or she analyzes a problem, how he or she proposes solutions, how he or she handles constraints or priorities.

Behavioral indicators make competence measurable and comparable.

Here is how to build a competency framework, step by step.

1. Clarify the purpose of the model

Before you write even a competency, you need to define why you need the model.

The key question for any HR is: What problems should it help you solve?

- Do you want to standardize interviews?

- Do you want to improve performance reviews?

- Do you want to build clearer growth paths?

- Or do you want to map internal skills to address future upskilling or reorganization needs?

A model only works if it is born with a concrete purpose. Without this initial clarity, it risks becoming a document that is perfect on paper but useless in practice.

2. Analyze roles and processes to understand what generates performance

This is the most important stage for an HR: to understand what skills really distinguish those who perform from average profiles.

In this sense, it is effective to combine:

- Observation of real work;

- Interviews with top performers;

- Analysis of performance and critical processes.

3. Building the catalog of corporate competencies

Once the insights have been gathered, it is time to translate them into a real catalog of skills.

This tool will then become the single reference for selection, evaluation and training.

The catalog should describe:

- technical skills;

- soft skills;

- managerial skills;

- expected values and behaviors

The most important part is not the name of the competency, but the operational definition: what does "collaboration" mean? How is "results orientation" recognized? What observable behaviors identify them?

4. Assigning skills to roles

Now the model must become operational. For each role, HR and managers must jointly define what skills are essential, what skills are distinctive, what level of mastery is required.

For example, it may be useful to supplement a set list with coded mastery levels:

- Level 1 Basic: applies the skill in expected and supported situations;

- Level 2 Intermediate: uses it independently in most situations;

- Level 3 Advanced: applies it in complex contexts, supports others, and helps improve processes;

- Level 4 Expert: Is an internal point of reference, trains others and guides strategic decisions.

This step creates a huge advantage: it allows you, as HR, to have a clear basis for selection, performance review, and growth path planning.

At the same time, it allows managers to understand exactly what to expect from a role while avoiding overlap, vagueness and unrealistic demands.

5. Validating the model with managers

One of HR's greatest difficulties is alignment with managers.

Validation by managers is precisely to verify that what you have defined really reflects daily work and that managers can recognize themselves in the model.

An HR can build a perfect model, but if managers do not use it, it will not generate any impact.

6. Choosing tools to assess competencies

Once the competency model is defined, comes the most delicate (and often most underestimated) step for any HR: measuring competencies objectively.

Many organizations build beautiful catalogs and detailed descriptions, but fall into the "trap" of evaluating it with overly subjective impressions.

To avoid bias or bias, you can integrate different tools:

- Structured interviews following the Behavioural Event Interview ( BEI) methodology;

- technical tests and practice trials;

- assessment center and simulations;

- Guided self-assessment.

How to make skill assessment objective with Skillvue

One of the biggest limitations of competency models is precisely the evaluation phase: if managers evaluate "by feel" or if HR does not have objective tools, all the work done upstream loses value.

Skillvue solves this problem by introducing a standardized, scientific and scalable approach:

- uses psychometric science and proprietary AI technology to assess technical, soft and management skills;

- integrates situational questions designed with the BEI method, which measure actual behaviors and not intentions;

- provides objective and comparable scores, eliminating bias and subjective interpretations;

- allows you to create a customized assessment aligned to your business competency model;

- returns a clear picture of candidates' or employees' potential and areas for development in just 15 minutes.

Start assessing skills and potential with real data: try Skillvue's Skill Assessments today.